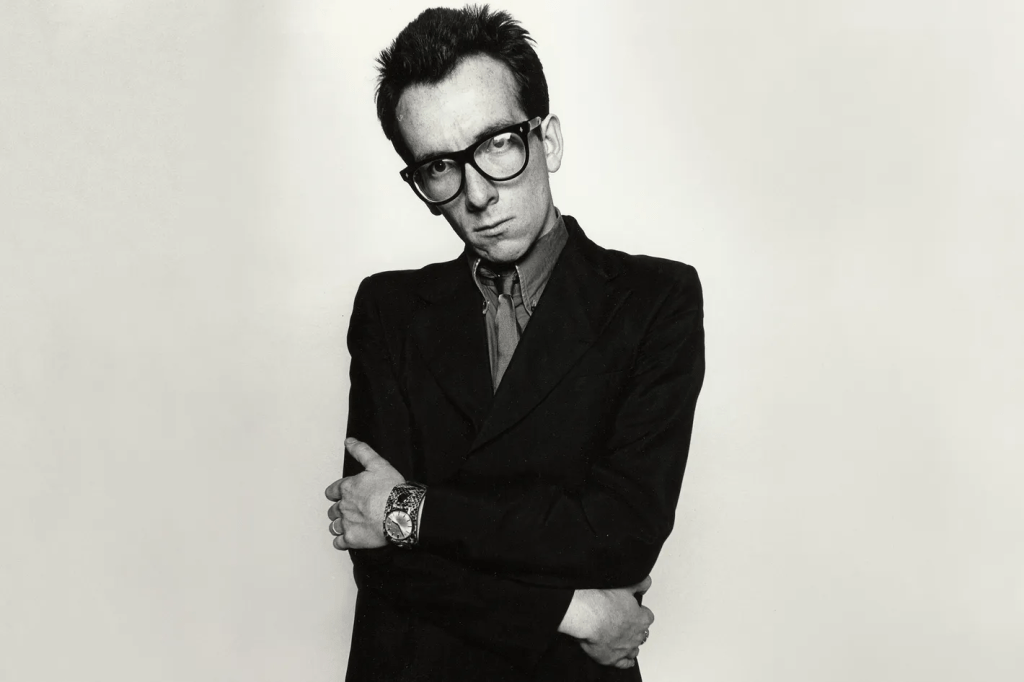

“This is Hell”, by Elvis Costello, from the “Brutal Youth” album of 1994, paints an unconventional, chilling yet darkly humorous picture of hell. Devils and flames are nowhere to be found (flames are mentioned, but only in absentia) and are replaced by visions evocative of humiliating memories, kitsch, and flamboyant bad taste.

All of these cringey, hyper saturated technicolor vignettes form the excruciating background of an eternity of embarrassment.

Costello suggests that hell is not what we may imagine – endless torture in an underworld of sulphur and pointy things prodding at you from all corners, but being forever condemned to relive these agonizing moments we’d all rather forget.

This hell is mostly located, it seems, in a bar or nightclub, where dancing and performance are involved:

“The bruiser spun a hula hoop

As all the barmen preen and pout

The neon “I” of nightclub flickers on and off

And finally blew out”

This “bruiser” could be a bouncer – or a particularly stout female performer. The barmen behave like haughy birds smoothing their feathers – their mustache or slicked-back hair, we can assume. The flickering neon ‘I’ may hint at how the ego itself falters in such an environment, dissolving into embarrassment and despair. The image is familiar – a common cinema trope – and evokes the cheap showiness of Las Vegas, Soho, and other famous adult amusement locales. These micro events or actions are recounted in a mix of past and present, Costello intimating, perhaps, that the immediate melts into the eternal in this gaudy underworld.

After the opening hulla-hoop number, the show moves on to more “exotic” territory, evoking stale oriental fantasies :

“The irritating jingle

Of the belly-dancing phony Turkish girls”

and the “phoniness” is enhanced by ultra violet lights, which pick out white surfaces, especially the artificially perfect smile of the dancers or – more probably – the wealthier members of the audience:

“The eerie glare of ultra violet

Perfect dental work”

The image, here again, is immediately familiar, and these disembodied, fake smiles push us further into a surreally sinister atmosphere, all the more threatening for its uncanny friendliness – much like the grinning Cheshire cat in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland. Bared teeth also unavoidably bring to mind grinning skeletons, as death, though never mentioned in the song, is lurking in the shadows of the nightclub.

In the chorus, Costello, directly addressing his listener, as he often does, makes two interesting and thought-provoking statements about hell – or damnation: first, it can’t improve or deteriorate, and the true horror lies in this permanent, mortifying mediocrity.

Secondly, hell is only the flip side of heaven, just like dystopia is that of utopia. In other words, the distinction between perfect, eternal bliss and relentless suffering is only paper thin. Also, certainly, Costello imparts that someone’s idea of paradise is another’s idea of psychological torture:

“This is hell, this is hell

I am sorry to tell you

It never gets better or worse

But you get used to it after a spell

For heaven is hell in reverse”

The second verse takes a closer look at the customers, among whom pathetic strategies of seduction are going horribly wrong:

“The failed Don Juan in the big bow-tie

Is very sorry that he spoke

For he`s mislaid his punch line

More than halfway through a very tasteless joke”

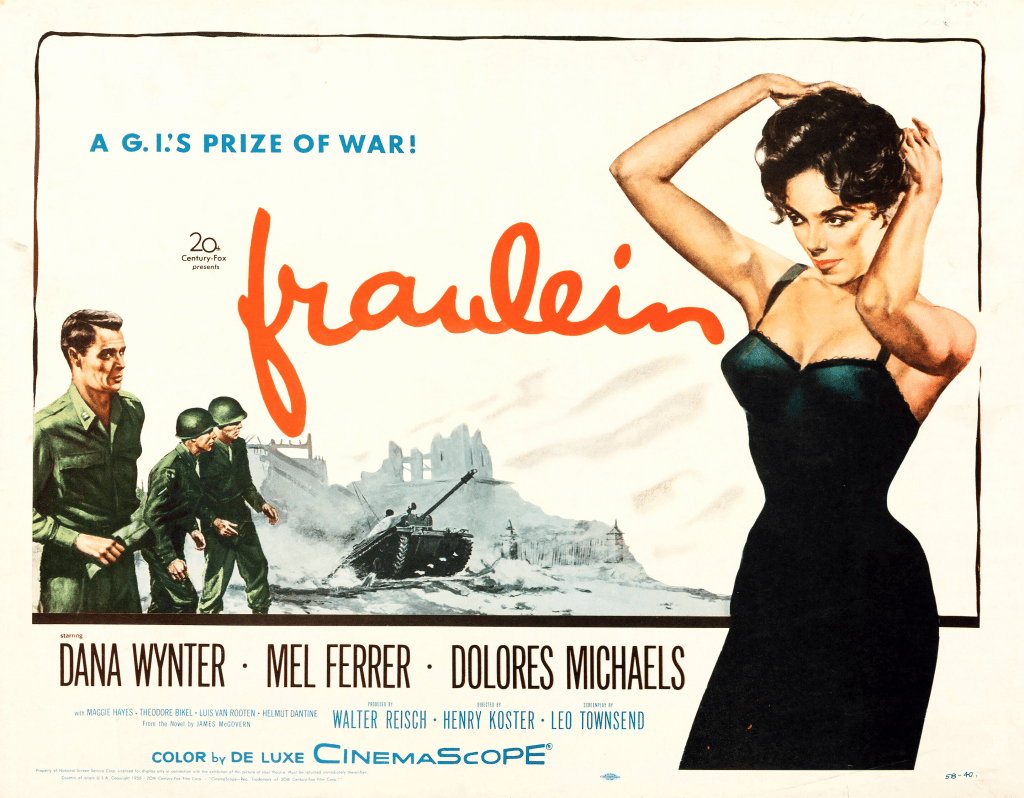

The “big bow tie” detail is merciless, making the failed Don Juan more of a sad clown – perhaps even senile, as he forgets the punch line to his joke – than a Casanova. “Fraülein” – the German word for an unmarried woman – evokes tawdry European exoticism:

“The Fraulein caught him peeking down her gown”

More specifically, in mid-20th century Anglo-American pop culture, “Fräulein” was a word tinged with wartime associations (GIs in occupied Germany getting romantically involved with stereotypical “German barmaids”), and later with cabaret imagery. As such, using the German term rather than “girl” strengthens the cheaply exotic, slightly cartoonish atmosphere, as though this hellish nightclub were a tacky international cabaret where national stereotypes are flattened into clichés.

The “Don Juan”’s awkward attempt at banter and sweet talking is exposed in its emptiness when the music stops:

“He’s yelling in her ear

And all at once the music stopped

As he was intimately bellowing “My dear…””

Here, the artificiality of dancefloor” intimacy” is revealed for the ludicrous social convention that it really is.

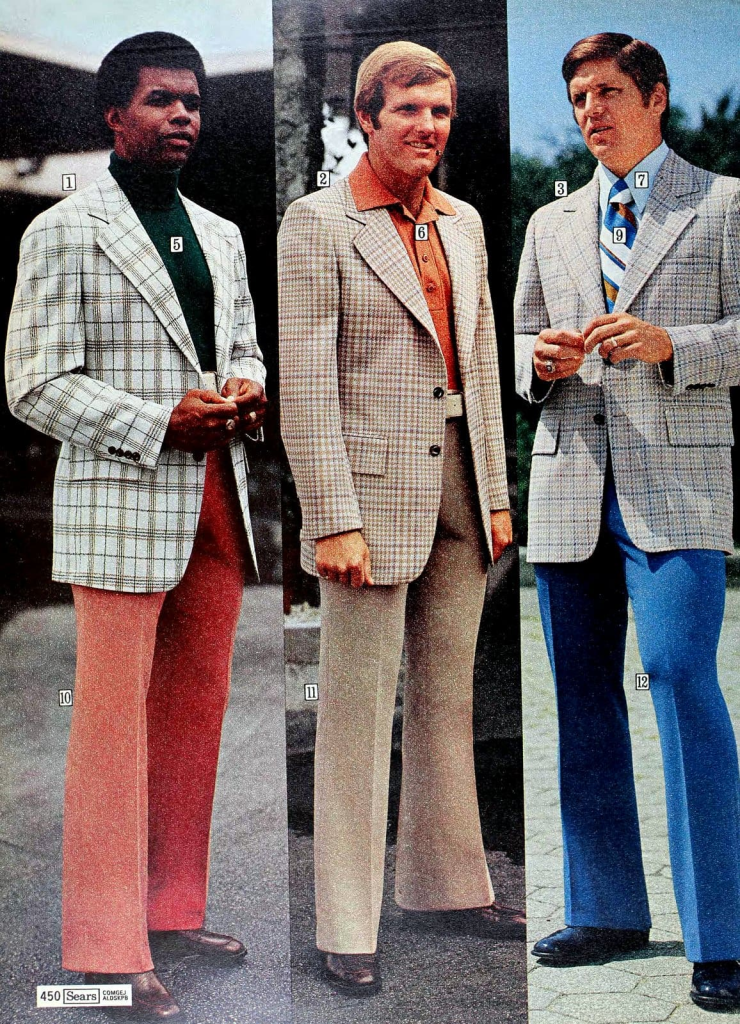

With the bridge, Costello operates a noticeable shift, delving into the listener’s (or the narratee’s) memories of questionable sartorial choices:

“The shirt you wore with courage

And the violent nylon suit

Reappear upon your back

And undermine the polished line you try to shoot”

The shirt was worn with courage, we may assume, because it was a bold, vain attempt at looking fashionable (there are plenty of photographs from the 1970s documenting, for instance, alarmingly pointy collars and loud flowery patterns) and the “nylon suit”, again a staple from the 60s and 70s, was a “violently” bold and offensive colour in retrospect. These ignominious garments reappear like the marks of an ancient curse, condemning the listener to endlessly relive his unfortunate fashion choices of the past. Costello condenses this notion, as well as the whole song’s essence, in the second half of the bridge:

“It’s not the torment of the flames

That finally see your flesh corrupted

It’s the small humiliations that your memory piles up

This is hell, this is hell, this is hell.”

Verse 3 moves away from the listener’s personal case, and returns to the atmosphere, which is now enlarged to that of a seaside hotel of some sort, where ambient numbing “feel-good” music is always on:

“”My Favorite Things” are playing

Again and again

But it’s by Julie Andrews

And not by John Coltrane”

Julie Andrews’ version – which is the original – contrasts, in its bland, almost annoying perkiness, with Coltrane’s much darker, sophisticated version.

Andrews’ version is the aural counterpoint to the equally bland tropes of middle to upper-middle class summer vacations:

“Endless balmy breezes and perfect sunsets framed

and the threadbare tokens of luxury and conventional commercialized decadence:

Vintage wine for breakfast

And naked starlets floating in Champagne”

The papier-mâché perfection of this underworld summer resort resonates with another, subtler terror, that of ageing, of having retired from the intense feelings, pleasures and pains of youth:

“All the passions of your youth

Are tranquillized and tamed

You may think it looks familiar

Though you may know it by another name”

The whole scene is indeed familiar in that it evokes outmoded fantasies and projections of blissful hedonism – an obsolete heaven perhaps, which, thanks to the narrator’s piercing stare and sharp pen, has completed its metamorphosis into hell.

In “This is Hell”, Costello deprives suffering and damnation of any dignity or grandeur, condemning the main character, addressed as “you”, to live eternally in a Babel of Faux-Cosmopolitanism furnished with the memories of a life of small humiliations. It recalls Sartre’s dictum l’enfer, c’est les autres in the way it repositions eternal punishment: not as confrontation with monstrous demons, but with other people’s banality—and with our own unbearable humanity, warts and all.

Leave a comment